Resource

Book Chapter: Achieving the UN SDGs Through the Integration of Social Procurement in Construction Projects

Sep 11th, 2023

This chapter, written by Buy Social Canada team members David LePage and Emma Renaerts, is an excerpt from the book “The Role of Design, Construction, and Real Estate in Advancing the Sustainable Development Goals,” edited by Thomas Walker (Concordia University), Carmen Cucuzzella (Université de Montreal), Sherif Goubran and Rana Geith (The American University in Cairo).

© The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2023

Introduction: Why Social Procurement?

Every purchase has an economic, environmental, cultural, and social impact, regardless of its size. Whether it be individual grocery choices, or government investment in a major infrastructure like a bridge, each choice entails many multipliers, ripple effects, and externalized consequences.

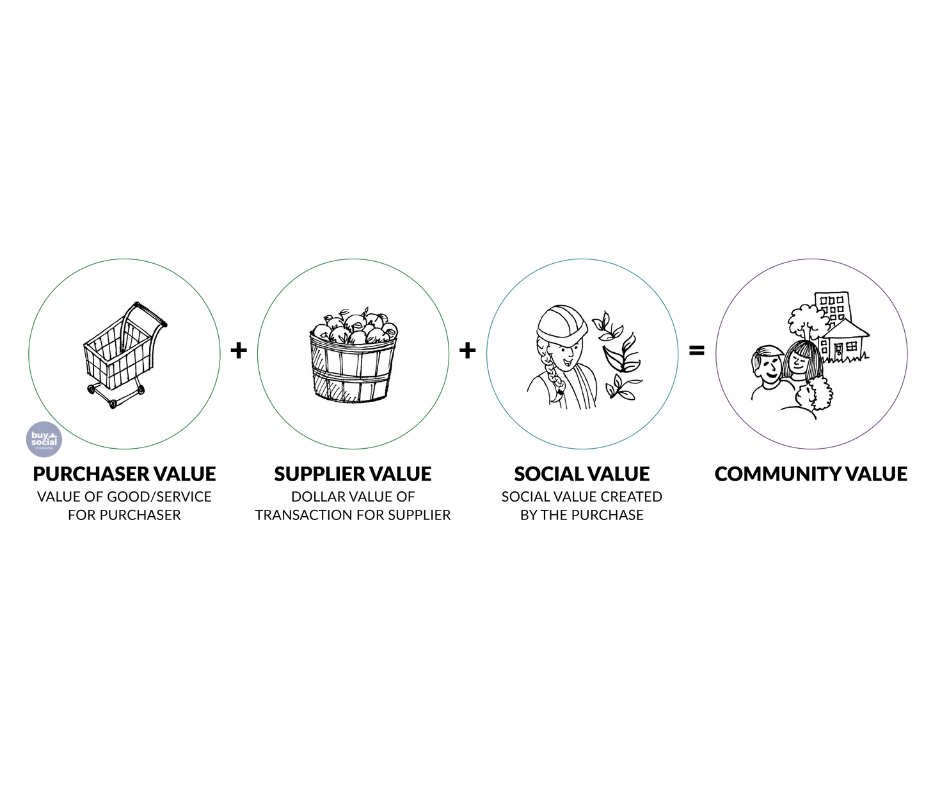

The power of the marketplace, when intentionally directed, has the potential to build not just economic value, but increase community capital, as shown in Fig. 1: healthy communities that are rich in human, social, cultural, physical, and economic capital.

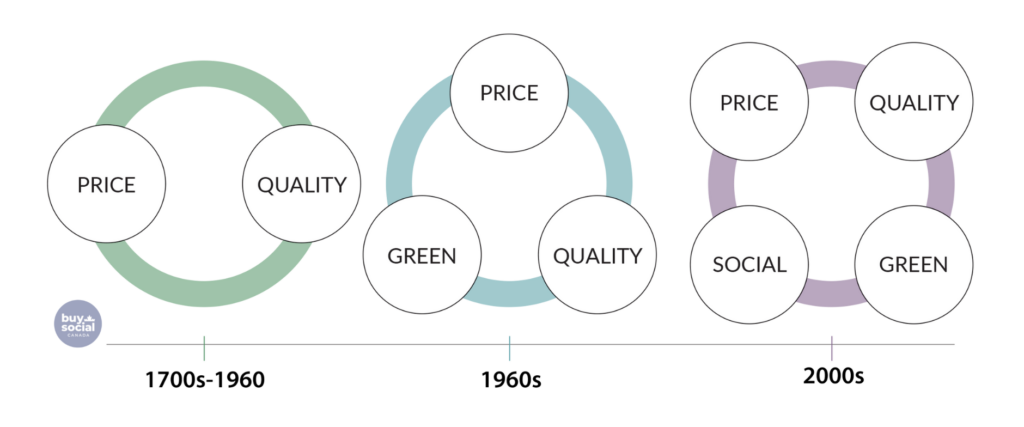

A social value marketplace focused on achieving measurable outcomes like the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will create communities that are inclusive, equitable, and diverse by offering training, employment, and social inclusion opportunities for every member of the community. In the last decade, as shown in Fig. 2, purchasers have increasingly considered the environmental impacts of their decisions.

In this chapter, we discuss the growing movement to add social value considerations to procurement decisions made in the construction industry, and we share case studies that demonstrate the power of procurement in construction to achieve multiple SDGs. Qualitative interviews with key figures from the organizations featured, along with research into relevant data and context, form the basis of the case studies presented below.

Social procurement, sometimes referred to as part of, or in terms of, sustainable procurement, asks how a purchase can help address and solve the complex socio-economic issues faced by a community. It seeks to consider where profits will go and how they will be used, who will be hired in the process, and who will provide the goods and services that go into the purchase. Simply put, it seeks to determine the community impact of the purchasing decision.

Figure 3 demonstrates how social procurement shifts marketplace value assumptions from considering purchasing as a purely economic transaction, trying to achieve the lowest price, to focusing on the power of the demand side of the market to drive positive social value outcomes. When we use social procurement to purchase goods, services, or choose a construction contractor, we’re deliberately balancing the environmental impact, the social value outcomes, the product or service requirements, and the price.

The large scale of the purchasing power of governments includes billions of dollars of spending every year on construction projects and infrastructure investments. From school repairs to building new fire-houses, road replacements, or new bridges, each of these projects requires hiring labor and purchasing a myriad of goods and services.

Building on the strength of their purchasing power, governments have become an early adopters of social procurement initiatives:

As the largest public buyer of goods and services, the Government of Canada can use its purchasing power for the greater good. We are using our purchasing power to contribute to socio-economic benefits for Canadians, increase competition in our procurements and foster innovation in Canada. (Public Services and Procurement Canada, 2020)

Across all levels of government, in several countries, including Canada, the United States, Scotland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Australia, policy is being designed and implemented to leverage existing purchasing or to use community benefit agreements to achieve social objectives and build community capital.

In general, over the past decade, we have witnessed the emergence of social procurement policies and initiatives across numerous entities as they adjust their historic purchasing criteria from lowest price to best value. Leveraging social value from existing buying offers an opportunity to solve persistent and complex social and environmental issues and work toward the accomplishment of the UN SDGs.

In Canada, Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) between parties such as owners, developers, general contractors, and community members require certain social outcomes on a specific construction or infrastructure project. They are now the policy of the federal government, several provincial governments, and multiple municipalities from Victoria to Halifax, Calgary, Edmonton, Toronto, and others.

Why Look to the Construction Industry to Achieve SDG’s?

The economic purchasing power of the construction sector is significant: “In many ways construction is the backbone of the Canadian economy. It employs 1.4 million Canadians and accounts for 7.5 percent of Canada’s GDP” (Canadian Construction Association, n.d.). Additionally, we know the “Canadian govern- ment will spend over $200 billion in the next ten years on infrastructure projects” (Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, 2022).

Imagine leveraging this enormous purchasing, hiring, and contracting power to not only build physical structures but to build community capital. This has already begun to happen. The construction industry is shifting from a business sector characterized as being driven by goals of “on budget and on time,” and dominated by white and male employees, to an industry that integrates principles of social procurement and diversity in employment, and which is responsive to community needs.

This shift means construction companies and purchasers can achieve multiple SDGs across the industry. The purpose of social procurement and community benefit models is to leverage the demand side of the construction industry market to achieve added social value.

As demand increases for social value suppliers and a diversified workforce, more social value is created. This global paradigm shift toward social procurement and community benefits in construction is a clear path to achieving multiple Sustainable Development Goals. From ending poverty to reducing the impacts of climate change, the construction industry holds a unique set of keys to influence these outcomes.

Buy Social Canada is a social enterprise that advocates for and supports the design and implementation of social procurement policies and programs. In our work across a wide spectrum of projects, we have identified four key social value outcomes that can be achieved when social procurement is integrated into construction projects: (1) jobs, (2) training and apprenticeships, (3) social value in the supply chain, and (4) additional community development goals.

Table 1 cross-references these outcomes with 12 SDGs which are most relevant to social procurement in construction. The construction industry addresses the SDGs when social procurement policies lead to collaboration with social value suppliers.

Additional Benefits of Implementing Social Procurement in Construction

This paradigm shift in procurement in the construction sector is being driven by multiple stakeholders who recognize the need for new processes and outcomes. A key element is the recognition that all levels of government and local communities around the world are experiencing severe and complex socio-economic issues such as unemployment, social exclusion, homelessness, youth disengagement, reconciliation with Indigenous populations, systemic racism, immigration, war, and poverty.

The construction industry also faces a serious worker shortage. The impending labor shortage is forcing a rethink of traditional construction labor market processes. The Canadian Construction Association reports that “about 21 percent of workers are set to retire over the next decade and the industry is struggling to attract the next generation of workers” (Canadian Construction Association, n.d).

Chandos Construction President Tim Coldwell adds: “Our industry has a huge problem. We are currently short 200,000 skilled workers, and 46% of our current labor force will retire in the next 10 years” (T. Coldwell, personal communication, July 15, 2022).

Another General Contractor states:

If we stick to the same old traditional approach we’ve used for 100 years, we won’t get anywhere. The diversity piece is the big benefit in terms of increasing our supply chain… We need different approaches and different options, thoughts, and experiences. (Buy Social Canada, 2022, pp. 53–54)

Adding in social value considerations can help to address these labor market shortages by tapping into a pipeline of new workers from historically marginalized or barriered groups, and sourcing new sub-contractors who deliver on social value.

The industry is also grappling with its environmental impacts, recognizing the ways waste and building materials contribute to climate change:

According to new research by construction blog Bimhow, the construction sector contributes to 23% of air pollution, 50% of climatic change, 40% of drinking water pollution, and 50% of landfill wastes. In separate research by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), the construction industry accounts for 40% of worldwide energy usage, with estimations that by 2030 emissions from commercial buildings will grow by 1.8%. (GoContractor, 2017)

Practicing social procurement processes which prioritize suppliers who are mitigating environmental impacts is one way the construction industry can begin to address this trend.

Social Value in the Supply Chain

Social enterprises are businesses that sell goods and services, embed a social, cultural, or environmental purpose into the business, and reinvest the majority of profits into their social mission. They provide a multitude of services to the construction industry supply chain, including staffing and labor, trailer cleaning, junk removal, printing and signage, catering and food trucks, security, couriers, and much more (in Canada, see the Buy Social Canada Directory of Certified Social Enterprises).

As most sites have multiple sub-contractors and trades on each project, providing jobs, creating training and apprenticeships, and using social value suppliers is not just the role of the primary contractor. Owners, general contractors, sub-contractors, and any others involved on a project should consider every opportunity available onsite to amplify social impact.

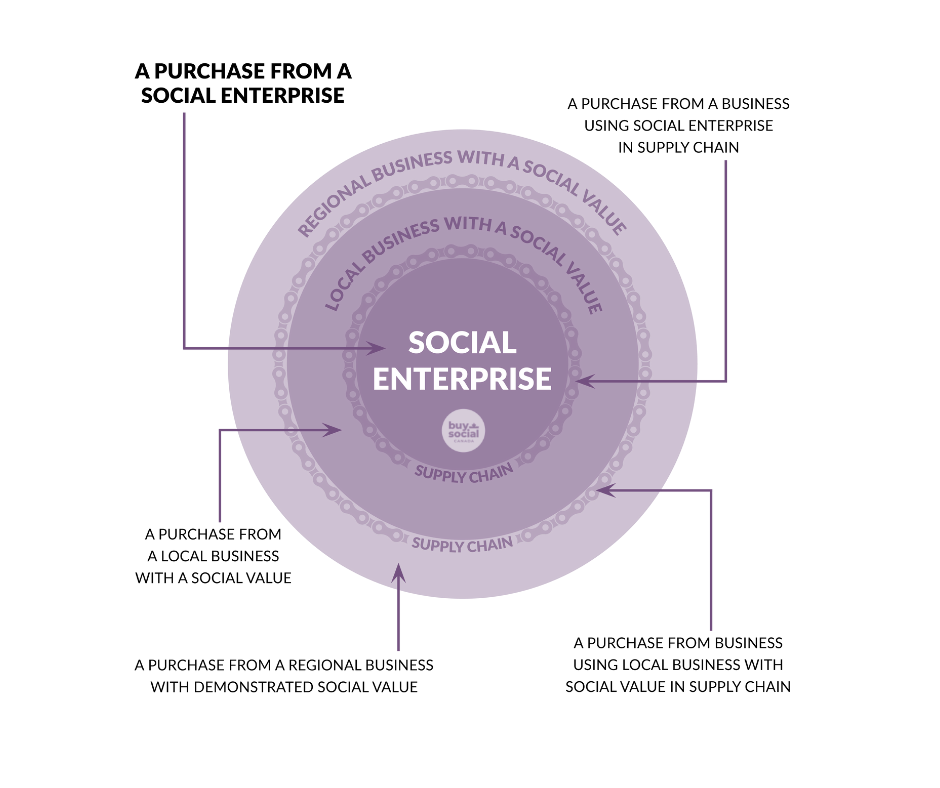

If a social enterprise is not immediately available, purchasers can use a concentric circle process (shown in Fig. 4) to look for other social value suppliers. Depending on their goals, this could be an Indigenous, Black, or women-owned business, a co-operative, a B Corp, or a locally owned or operated business.

Case Study: EMBERS, Supportive Employment, and Community Economic Development

EMBERS, the Eastside Movement for Business and Economic Renewal Society, is a social enterprise and registered community economic development charity located in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, one of Canada’s poorest neighborhoods. Since its founding in 2001, EMBERS has worked to create economic and employment opportunities for people living on low incomes (EMBERS Canada, n.d.).

In 2008, to further this mission, they started EMBERS Staffing Solutions, a non-profit staffing agency, “placing all of [their] profit back into our workers through services like training, free equipment rental, and transportation” (EMBERS Staffing, n.d.). Their work has been recognized with many awards and accolades, including a 2021 Governor General’s Innovation Award (Gov- ernor General’s Innovation Awards, 2021).

“Our focus is to work with people who are not necessarily conditioned to ‘normal’ 9–5 work or middle-class life, what is expected when you think of work. We’re working with people who are learning how to get back and develop a sustainable income,” CEO and Founder of EMBERS, Marcia Nozick, told Buy Social Canada in an interview. “Our social enterprise model can meet people where they’re at” (M. Nozick, personal communication, June 15, 2022).

Construction companies have been valuable partners for EMBERS. Most EMBERS employees are placed in construction jobs, which are uniquely suited to support people looking to re-enter the workforce and start with what they’re able to manage. Construction companies tend to use a lot of contingent labor, and most projects have different stages where various kinds of labor are needed. “As a result, you can work with that to mold something to fit the right person to the right job,” says Nozick.

Construction is also a great workplace for EMBERS employees, Nozick shares, because it is easy to “ladder up” to a career over time. EMBERS has seen several people go from general work on sites, to eventually become site supervisors. One such employee is Neil (name changed to protect anonymity). Nozick shares that Neil had experienced severe trauma in his life. An immigrant to Canada, he lost his family in tragic circumstances and now struggled with anxiety and other mental health issues. For many years, he could not work at all. After several years of treatment, however, his counselor recommended he work with EMBERS.

“He had the greatest attitude,” says Nozick. Starting on site as a general laborer, Neil had a rocky beginning, sometimes showing up, sometimes not. One day, Nozick says, Neil realized, “actually work makes me feel better, work is my therapy.” Gradually, he began to work more steadily and was able to take several training courses with support from EMBERS. He qualified as a hoist operator, and then a construction safety officer.

After three years of working with EMBERs, Neil’s talents and dedication were recognized by a large construction company, who hired him full-time and is planning to put him through school to further his career development. He is now the head construction safety officer of his company, and in his role, he employs more EMBERS workers. He told Nozick that EMBERS saved his life.

Another EMBERS employee who was able to build a career in construc- tion is Mike (name changed to protect anonymity). When Mike first started with EMBERS, he had just left treatment for a drug addiction and was homeless. No one would hire him until he was referred to EMBERS. “We had him working the very next day,” Nozick says, “and Mike never looked back.” Today, Mike is a site superintendent for a local construction company, and he has since re-married and bought his own apartment.

Every year, EMBERS employs 2,500 people with stories like Neil’s and Mike’s, and “every one of those people need[s] a job,” says Nozick. The work they do achieves many Sustainable Development Goals, most notably: SDG 1, No Poverty; SDG 4, Quality Education; SDG 8, Decent work and Economic growth; and SDG 11, Sustainable Cities and Communities.

In addition to creating opportunities for many who are unemployed or under- employed and providing training and wrap-around support to them, EMBERS, as a social enterprise, also re-invests the majority of its profits back into the community. One key lever that enables EMBERS to achieve these out- comes is social procurement. “Social procurement opens up opportunities for us as a social enterprise to grow,” says Nozick, “it really help[s] to build our foundation.”

Nozick also notes that social procurement, for example, under the City of Van- couver’s Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) Policy, “encourages patience on the part of the contractor,” because they are willing to work with social value suppliers and create some space for employees with barriers, as part of their con- tract requirements on a project. “We wouldn’t be successful without companies buying in,” says Nozick, “and social procurement is one of those ‘tying-together’ pieces that helps communities connect. I think it’s a really great strategy.”

Construction companies can choose from many temporary labor services, but only EMBERS offers a full program of employee support (including training, insurance, good wages, and even encouragement) to help their workers to move on to full-time permanent work through collaborative programs with their busi- ness clients. Neil and Mike’s stories serve to illustrate and corroborate the fact that the collective activities of EMBERS achieve at least a dozen of the UN SDGs every day, an effect that would be amplified if similar concepts were adopted globally.

In Canada alone, there are many other effective construction social enterprises seeking to create healthy communities and support people through employment. BUILD, a social enterprise in Winnipeg, Manitoba, trains and employs youth at risk in the building trades. Build Up Saskatoon offers steady employment, mentorship, and other social supports to their employees to aid them to achieve meaningful, long term employment in the construction industry. Building Up in Toronto works with persons facing barriers to enable them to enter the labor market through jobs in the construction industry. Impact Construction in St. John’s, Newfoundland, has built their business model around supporting youth to gain skills and build a successful future.

The same trend is happening globally. Veterans in Construction in Melbourne, Australia, is “a Veteran owned and operated company […] committed to providing long-term sustainable employment opportunities to Veterans within the construction industry” (Veterans in Construction, n.d.). In London, Bounce Back trains and employs people leaving prison to enter construction jobs. And in Mexico, Echale a Tu Casa trains people in construction skills, while helping to build affordable homes for Mexico’s poorest communities.

Policy as a Driver for Change

Governments at all levels and in multiple countries see the opportunity and the need to leverage social value outcomes to meet their social goals and to address equity, social inclusion, poverty, climate change, and more, all of which align with the UN SDGs. As mentioned earlier, the city of Vancouver, British Columbia, has a mandatory Community Benefit Agreement (CBA) Policy which requires large, rezoned development projects to include the creation of specified local and social jobs and the inclusion of a diverse and social value supply chain (City of Vancouver, n.d.).

Canada’s Federal Ministry of Infrastructure has adopted a Community Employment Benefits program to promote increased employment opportunities “for a broader array of Canadians” (Government of Canada, n.d.). In Scotland, the Public Reform Act is used “to improve the economic, social or environmental wellbeing” of the communities in which construction projects occur (Scottish Government, n.d.).

As Government policy increasingly requires proponents to create social value from construction projects, we see that “the evidence of best value through procurement is still a nascent movement, with a need to address pre-existing perceptions through research and case study evidence”(Buy Social Canada, 2022). Some early criticism from industry sees the emerging policies as extortion for social value, a distraction, or merely an added cost: “This survey of CBAs points to the tantalizing potential of a good idea […] there is much work to be done if CBAs are to truly achieve their promise”(Cardus, 2021).

Dr. Daniela Troje interviewed key actors in the Swedish construction sector and reviewed policy-in-practice literature. She concluded that while social procurement policies can mitigate issues connected to social exclusion, unemployment, and segregation, and that while the construction sector holds opportunities for social procurement, there is currently a misalignment among social procurement policies (Troje, 2021).

In their 2021 research on champions of social procurement in the Australian construction industry, Loosemore, et al. find that:

There has been a recent proliferation of social procurement policies in Australia that target the construction industry. This is mirrored in many other countries, and the nascent research in this area shows that these policies are being implemented by an emerging group of largely undefined professionals who are often forced to create their own roles in institutional vacuums. (Loosemore, Keast, Barraket, et al., 2021)

Though the movement is still in its early stages, it already serves as proof that policy has the power to influence change and help achieve the UN SDGs in the construction industry.

Case Study: Chandos Construction: Policy as a Competitive Advantage and Value for the Construction Sector

Chandos Construction is an exemplary business within the construction industry. Established in 1980, they were founded from the beginning with a vision to “be a business that balances both profits and people” (Chandos Construction, n.d. b). A company of over 600 employees spanning seven locations across Canada, they are the first and largest B Corp certified national technical builder in North America and are 100 percent employee-owned (Chandos Construction, n.d. b).

Chandos is working toward achieving many UN SDGs in their work. Early adopters of social procurement in the construction sector, they signed on as founders of the Buy Social Canada Pledge in 2020, committing to “shift at least five percent of [their] addressable spend to social enterprises, diverse-owned businesses, and other impact organizations by 2025” (Chandos Construction, n.d. c).

In 2022, they announced an additional commitment to become Net Zero by 2040, working toward increased sustainability and reduced environmental impacts (Chandos Construction, n.d. a). President Tim Coldwell, states that the top three SDGs Chandos focus on through their work are SDG 8, Decent Work and Economic Growth; SDG 1, No Poverty; and SDG 4, Quality Education.

Through social procurement, Chandos uses its labor force to provide employment opportunities for local people from equity-deserving groups (Chandos Construction, n.d. c). Its aim is to:

- Expand diversity in local businesses.

- Reduce poverty and strain on the Canadian social system.

- Provide work, offer skills training, and pay fair wages to people from equity- seeking groups.

- Support businesses that are working toward the goals of the Paris climate agreement.

In a qualitative interview with Buy Social Canada, Coldwell shared the many ways that inclusive hiring can achieve the SDGs, and save taxpayer money:

We often will hire an at-risk youth who is [sic] 17–18 years old. If you believe that person was heading toward the criminal or social support system, and instead they are now making money and paying taxes, while also saving the government thousands in social supports, that can be an impact of $400,000 per person. (T. Coldwell, personal communication, July 15, 2022)

Chandos is in an interesting position in the supply chain to achieve the SDGs and be impacted in turn by other purchasers who are working toward social and sustainable value outcomes. Chandos can address its own supply chain decisions, increasing the benefits it delivers to communities through its purchasing practices, but the company also benefits from social procurement policies as a B Corp and social purpose business that is able to assist other purchasers to meet their own goals for sustainable development.

Chandos Construction leadership has seen their commitments to social procurement and sustainability rewarded in an increase in contracts. Coldwell shares that in 2021, out of $800 million in total sales, they won approximately $350 million “because of our leadership on this.”

He adds that “We were not the lowest fee on approximately $300 million of it,” and that “we are winning work we wouldn’t have won, with a premium fee, because of the social value we deliver.”

One noteworthy example of this phenomenon is the Rundle Affordable Housing Project in Calgary, Alberta, which Director of Business Development Robert Cowan believes Chandos won largely because of the weighted social value criteria in the Request for Proposals (RFP) which was issued in late 2021 (R. Cowan, personal communication, June 14, 2022).

The City of Calgary began implementing Benefit Driven Procurement (BDP) (also referred to as social procurement) in 2019, “seeking to make intentional positive contributions to both the local economy and the overall vibrancy of the community” (City of Calgary, n.d.). On the Rundle Project, the city was asking what proponent general contractors could deliver in terms of diverse hiring, Indigenous inclusion, living wages, and environmental sustainability.

“Rundle was the first time I had seen the City of Calgary requesting these things for a major project,” Cowan told Buy Social Canada in an interview. “It was encouraging to see a major player like Calgary, that had previously been predominantly decided based on dollars and cents, incorporate social procurement into their procurement practice.”

Cowan adds that in recent years, Chandos has seen an increase in social procurement policies and practices in municipalities and government organizations throughout Western Canada and in Ontario, as well as among private clients across Canada. Although they may not all use the language of social procurement, purchasers are increasingly demonstrating that social value outcomes are important to them in both their requests for proposals and interview questions with proponents.

Cowan is hopeful about this trend, reflecting that, “it wasn’t that long ago where sustainability wasn’t considered, and there was a time when safety wasn’t even considered. That was a new question 30 years ago … and now safety is table stakes for construction,” and that “social procurement and what companies are doing beyond just building things […] 30 years from now in my opinion, that will be table stakes.”

Policy is a valuable tool to overcome the stigma and myths surrounding social procurement in the construction industry. Cowan has seen cases when companies are forced to practice social procurement as a requirement of their contract on a construction or infrastructure project, and then come to the realization that their preconceptions were wrong.

The City of Calgary’s BDP Policy, for example, has had a massive impact in the region due to its influential position in the supply chain. Cowan shares that years ago, the social value methods of Chandos Construction were questioned by many. Those who questioned Chandos in the past are taking a second look, as large purchasers such as Calgary award points that require specific outcomes that Chandos is already well positioned to deliver.

“What’s encouraging is that people are adopting this, and look at things differently,” says Cowan. “Obviously there’s a competitive advantage, we’re still a business, we’re still a construction company, we have 600 employees that need to get paid. But if we can have a competitive advantage that influences the rest of our industry to think about things differently at the same time, and eventually in 10 years if everyone is acting this way, I don’t know if there’s a greater outcome for it.”

While Chandos has certainly secured a competitive advantage in a market that increasingly prioritizes social and environmental outcomes, their main intent is not a competitive advantage, Cowan allows: “it’s to influence and positively impact our communities through our position in the supply chain.”

Company President, Tim Coldwell sums it up well:

Policies create demand and push contractors to practice social procurement. We need the whole industry to focus on it. The big volume buyers of construction making these moves is a great way to push industry to do this and to learn that it’s not as hard as they think. (T. Coldwell, personal communication, July 15, 2022)

What often begins with resistance and strictly as a matter of compliance can lead to a change in relationships between market segments. This is currently the case developing in social procurement and community benefit agreements across the construction sector: from fear and myths about the process to engagement, pilots, and early successes. When compliance becomes a market advantage in meeting social value requirements built into RFx and contract deliverables, the industry adapts.

Chandos Construction is not alone in its leadership. Other construction companies are also stepping up to create change through social procurement. Bird Construction, a Buy Social Engage Member, has partnered with Chandos to support the Building Good initiative to innovate the construction sector for increased social impact. Other Buy Social Canada Social Purchasing Partners from the construction sector who have made a commitment to social procurement in their organization and supply chain include Clark Builders, Delnor Construction, and michael + clark construction.

Looking Ahead

With the integration of social procurement and community benefit agreements in construction, we are transitioning from an industry whose purpose was to merely build structures “on time and on budget” to an industry that is building healthy communities and achieving multiple UN SDGs.

This emerging framework is being led, on the supply side by social enterprise suppliers like EMBERS, and, on the demand side through supportive public policy at all levels of government and by social value purchasers like Chandos Construction. We are witnessing a culture shift across the construction sector. This model uses existing construction contracts and infrastructure investments to achieve the SDGs through employment opportunities, training and apprenticeships, and supply chains that are inclusive of social values: diversity, equity and inclusion.

The challenge, and the imperative, is to continue the journey along this path. To move the story from a few cases like Mike and Neil to a multitude of evidence-based social value goals and measurable results. Each time a social value construction company adds targeted jobs, increases apprenticeships for per- sons facing barriers to employment, and brings new social enterprises into their supply chain, we have the potential to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the opportunity to build healthy communities.

Bibliography

Atkinson Foundation. (2016). Making community benefits a reality in Ontario. https://img1. wsimg.com/blobby/go/155a0c21-72da-4b9c-bddb-4e2a3a316ead/downloads/Atkinson_ CBSummary_FA-1-2.pdf?ver=1632423831411

Barraket, J., & Loosemore, M. (2018). Co-creating social value through cross-sector collaboration between social enterprises and the construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 36(7), 394–408.

Bateman, J. (2020). More British Columbians support community benefits agreements. Independent Contractors and Businesses Association of BC. https://www.icbaindependent.ca/ 2020/06/11/news-release-poll-shows-overwhelming-support-for-fair-bidding-in-b-c/

Buy Social Canada. (2019). Social procurement policy framework.

Buy Social Canada. (2022). Voices of industry: A paradigm shift in CBAs. https://www.buysocialcanada.com/wp-content/uploads/Voices-of-Industry-Paradigm-Shift-in-CBAs.pdf

Canada’s Building Trades Unions. (2022). Community benefits agreements. Retrieved September 26, 2022, from https://buildingtrades.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/CBA- Report.pdf

Canadian Construction Association. (n.d.). Workforce. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https:/ /www.cca-acc.com/advocacy/critical-issues/construction4cdns/workforce/#:~:text= The%20industry%20is%20facing%20a,Canadian%20Construction%20Association% 20(CCA)

Canseco, M. (2020). More British Columbians support community benefits agreements. https:/ /researchco.ca/2020/06/01/cba-btc/

Cardus. (2021). Community benefits agreements: Toward a fair, open, and inclusive framework for Canada. Retrieved September 26, 2022, from https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/community-benefits-agreements-toward-a-fair-open-and-inclusive-framework-for-canada/

Cautillo, G. (2020, November 30). OGCA viewpoint: What are community benefits anyway? Ontario Construction News. https://ontarioconstructionnews.com/ogca-viewpoint-what- are-community-benefits-anyway-2/

Centre for Social Impact Swinburne. (2021). Research roundtable on social and indigenous preferential procurement. https://assets.csi.edu.au/assets/research/Research-Roundtable-on-Social-and-Indigenous-Preferential-Procurement-Summary-Report.pdf

Chandos Construction. (n.d. a) Net zero 2040. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://www. chandos.com/who-we-are/netzero/

Chandos Construction. (n.d. b) Our story. Retrieved July 25, 2022a, from https://www.cha ndos.com/who-we-are/our-story/

Chandos Construction. (n.d. c) Social procurement. Retrieved July 25, 2022b, from https:// www.chandos.com/how-we-build/social-procurement/

City of Calgary. (n.d.). Benefit driven procurement. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https:// www.calgary.ca/cs/supply/supplyhome/benefit_driven_procurement.html

City of Vancouver. (n.d.). Community benefit agreements policy. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://vancouver.ca/people-programs/community-benefit-agreements.aspx

Denny Smith, G., Loosemore, M., & Williams, M. (2020). Assessing the impact of social procurement policies for indigenous people construction management and economics, 38(12), 1139–1157. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01446193.2020.1795217

Denny-Smith, G., & Loosemore, M. (2017). Integrating indigenous enterprises into the Australian construction industry. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 24(5).

Denny-smith, G., Sunindijo, R. Y., Loosemore, M., Williams, M., & Piggott, L. (2021). How construction employment can create social value and assist recovery from covid-19. Sustainability (switzerland), 13(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020988

Dragicevic, N., & Ditta, S. (2016, April). Community benefits and social procurement policies: A jurisdictional review. Mowat Centre. https://www.cardus.ca/research/work- economics/reports/community-benefits-agreements-toward-a-fair-open-and-inclusive-framework-for-canada/

EMBERS Canada. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://emberscanada.org/ about/

EMBERS Staffing. (n.d.). Embers staffing: A division of Embers. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://embersstaffing.com/about/

GoContractor. How does construction impact the environment? (2017, June 21). https://goc ontractor.com/blog/how-does-construction-impact-the-environment/

Government of Canada. Community Employment Benefits Guidance. (n.d.) Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/pub/other-autre/ceb-ace-eng. html

Governor General’s Innovation Awards. (2021). Embers staffing solutions. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://innovation.gg.ca/winner/embers-staffing-solutions/

Graser, D. (2016). Community benefits in practice and in policy: Lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom.

Graser, D. (2018). Community benefits in York region research report.

Gunton, C., & Markey, S. (2021). The role of community benefit agreements in natural resource governance and community development Issues and prospects, 73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102152

Gunton, C., Gunton, T., Batson, J., Markey, S., & Dale, D. (2021). Designing fiscal regimes for impact benefit agreements, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102004

Inclusive Recovery. (n.d.). FAQs. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.inclusiverec overy.ca/faqs

Kucheran, R. (2020). Industry perspectives op-ed: Investing in infrastructure must mean investing in Canadians. https://canada.constructconnect.com/dcn/news/government/ 2020/06/industry-perspectives-op-ed-investing-in-infrastructure-must-mean-investing-in-canadians

LePage, D. (2014). Exploring social procurement: Accelerating Social Impact CCC, Ltd. https://ccednet-rcdec.ca/sites/ccednet-rcdec.ca/files/ccednet/exploring-social-procurement_asi-ccc-report.pdf

Let’s Build Canada. (2021, September 9). New survey finds construction workforce’s top election priorities include supports for workers, changes to EI, labour mobility, and transition to Net Zero. https://www.letsbuildcanada.ca/newsroom/new-survey

Loosemore, M. (2016). Social procurement in UK construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 34(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015. 10.005

Loosemore, M. (2019). Social procurement in the construction industry: Challenges and realities.

Loosemore, M., & Bridgeman, J. (2017a). Corporate volunteering in the construction industry motivations, costs and benefits. Construction Management and Economics, 35(10), 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2017.1315150

Loosemore, M., & Bridgeman, J. (2017b). The social impact of construction industry schools-based corporate volunteering. Construction Management and Economics, 36(5), 243–258.

Loosemore, M., & Higgon, D. (2015). Social enterprise in the construction industry: Building better communities.

Loosemore, M., & Reid, S. (2019a). The social procurement practices of tier-one construction contractors in Australia. Construction Management and Economics, 37(4), 183–200.

Loosemore, M., Alkilani, S., & Mathenge, R. (2020a). The risks of and barriers to social procurement in construction: A supply chain perspective. Construction Management and Economics, 38(6), 1–18.

Loosemore, M., Alkilani, S., & Mathenge, R. (2020b). The risks of and barriers to social procurement in construction a supply chain perspective. Construction Management and Economics, 1–18.

Loosemore, M., Bridgeman, J., & Keast, R. (2020c). Reintegrating ex-offenders into work through construction a case study of cross-sector collaboration in social procurement. Building Research & Information, 48(7). https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2019.169 9772

Loosemore, M., Denny-Smith, G., Barraket, J., Keast, R., Chamberlain, D., Muir, K., Powell, A., Higgon, D., & Osborne, J. (2020d). Optimising social procurement policy outcomes through cross-sector collaboration in the Australian construction industry Emerald Insight. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 28(7).

Loosemore, M., Higgon, D., & Osborne, J. (2020e). Managing new social procurement imperatives in the Australian construction industry. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 27(10), 3075–3093.

Loosemore, M., Osborne, J., & Higgon, D. (2020f). Affective, cognitive, behavioural and situational outcomes of social procurement a case study of social value creation in a major facilities management firm Construction Management and Economics, 39(3), 227–244.

Loosemore, M., Alkilani, S., & Ahmed, A. (2021a). The job-seeking experiences of migrants and refugees in the Australian construction industry Building Research & Information. Building Research & Information, 49(8). https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2021.192 6215

Loosemore, M., Alkilani, S., & Hammad, A. (2021b). Barriers to employment for refugees seeking work in the Australian construction industry an exploratory study Emerald Insight. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 29(2). https://www. emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ECAM-08-2020-0664/full/html

Loosemore, M., Alkilani, S., & Murphy, R. (2021c). The institutional drivers of social procurement implementation in Australian construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 39(7), 750–761.

Loosemore, M., Bridgeman, J., Russell, H., & Alkilani, S. Z. (2021d). Preventing youth homelessness through social procurement in construction: A capability empowerment approach. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063127

Loosemore, M., Keast, R., Barraket, J., & Denny-Smith, G. (2021f). Champions of social procurement in the Australian construction industry: Evolving roles and motivations. Buildings, 11(12), 641. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11120641

Macfarlane, R. (2014). Tackling poverty through public procurement. www.anthonycollins. com/briefings/social-value-and-public-procurement

Macfarlane, R., & Joseph Rowntree Foundation. (2000). Using local labour in construction: A good practice resource book. Policy Press.

MoneyWellWasted.Ca. (n.d.) Fake CBA – Money well wasted. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://moneywellwasted.ca/fake-cba/

Mustafa, H., & Sengupta, R. (2014). Connecting capital to sustainable infrastructure opportunities white paper for sustainable infrastructure symposium.

Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. (2022, March 3). Federal Infrastructure Spending, 2016–2017 to 2026–2027. https://www.pbo-dpb.ca/en/additional-analyses–analyses-complementaires/BLOG-2122-008–federal-infrastructure-spending-2016-17-2026-27–depenses-federales-infrastructure-2016-2017-2026-2027#:~:text=On%20a%20Public% 20Accounts%20(accrual,%2422.8%20billion%20in%202020%2D21

Office of the Procurement Ombudsman. (2020, September). Social procurement: A study on supplier diversity and workforce development benefits. https://opo-boa.gc.ca/diversite-diversity-eng.html

Public Services and Procurement Canada. (2020). Advancing socio-economic goals, increasing competition and fostering innovation—Better Buying—Buying and selling. https:// www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/app-acq/ma-bb/posacfi-asgicfi-eng.html

Raiden, A., & Loosemore, M. (n.d.). Social value in the built environment. Routledge & CRC Press.

Raiden, A., Loosemore, M., King, A., & Gorse, C. (2018). Social value in construction Ani Raiden, Martin Loosemore, Andrew Ki. 238. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315100807

Scottish Government. Community benefits in procurement. (n.d.) Retrieved September 23, 2022 from https://www.gov.scot/policies/public-sector-procurement/community-benefits-in-procurement/

Toronto Community Benefits Network. (2020). TCBN stakeholder consultation report for career track in construction project.

Troje, D. (2021). Policy in practice: Social procurement policies in the Swedish construction sector. Sustainability (switzerland), 13(14), 7621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147621 Veterans in Construction. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://veteransinconstruction.com.au/

Williamson, A. (2021). Which community benefits agreements really delivered? Shelterforce.

Yalnizyan, A. (2017). Community benefits agreements empowering communities to maximize returns on public infrastructure investments. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34404.